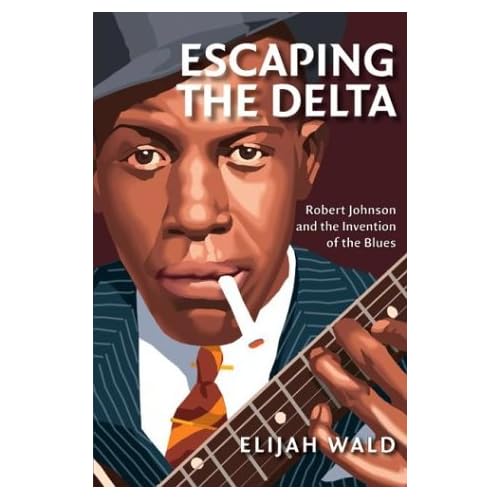

Robert Johnson

and the Invention of the Blues

please click image

According to Publishers Weekly;

In this combination history of blues music and biography of Robert Johnson, Wald, a blues musician himself (and author of Narcorrido), explores Johnson's rise from a little known guitarist who died in 1938 to one of the most influential artists in rock and roll. From the blues' meager beginning in the early 1900s to its '30s heyday and its 1960s revival, Wald gives a revisionist history of the music, which he feels, in many instances, has been mislabeled and misjudged. Though his writing sometimes reads like a textbook, and he occasionally gets bogged down in arcane musical references, Wald's academic precision aids him in his quest to re-analyze America's perception of the blues as well as in trying to decipher the music's murky true origins and history. Using a lengthy comparison of how white Americans and black Americans define the blues, Wald demonstrates how Johnson fit into the gray area between the two. Wald combines a short bio of Johnson with detailed analysis of his songs and the mysterious tales that are associated with him, giving a thorough account of Johnson's life, music and legend. The chapter on how white guitarists like Eric Clapton and Keith Richards interpreted who Johnson was and what he played really shows why he is not one of the many forgotten early 20th-century bluesmen. Wald's theories will no doubt cause passionate discussions among true blues aficionados, but the technical and obscure nature of much of his writing will make the book more of a useful reference resource.

The Washington Post gave this review;

The congressional proclamation of 2003 as the "Year of the Blues" enabled all manner of film, concert and educational initiatives meant to raise public awareness and appreciation of a genre that Congress asserts "is the most influential form of American roots music." While few would argue otherwise, some have responded to all this Capitol Hill pomp by raising questions about the relevance of the blues in the 21st century, when the music's audience has skewed overwhelmingly white, and its most rabid supporters appear to be the fraternity of beer-ad music supervisors.

Elijah Wald is not so interested in what the blues means in its year of distinction, but he is very interested in how it came to mean something other than what it once did. In Escaping the Delta, he sets out to explore "the paradox of [Robert] Johnson's reputation: that his music excited so little interest among the black blues fans of his time, and yet is now widely hailed as the greatest and most important blues ever recorded." Wald sees this paradox as symbolizing a larger gulf between the blues as heard by the black audience in its own time -- who knew it as hip, popular music -- and a later, mostly white audience that romanticized the blues as "the heart-cry of a suffering people." Not a book about Johnson per se, Escaping the Delta is a thoughtful, impassioned historical essay about that gulf.

Wald spends the first several chapters laying out the prewar musical terrain in which the blues came to the fore, through a synthesis of murkily understood received culture and the skills of those who refined the blues into a consciously commercial -- not naively folk -- art. After a quick sketch of Johnson's life and a critical analysis of his recordings, Wald carries the story through to the folk-revival "discovery" of the blues in the 1950s and the British Invasion's canonizing stamp of the 1960s, then adds a coda in which he seeks to lay permanently to rest the resilient myth that Johnson met the devil at a crossroads and sold his soul for other-worldly musicianship.

If the first half of the story sounds a lot more interesting than the second, Wald may feel the same way. Escaping the Delta is most engaged in the early going, as he dismantles genre stereotypes via endearing tidbits such as that blues singer Memphis Minnie's set list included George Gershwin's "Lady Be Good" and that Johnson rated the Sons of the Pioneers' "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" among his favorite songs. The book is much more hurried and polemically loose on the downhill side, as Wald takes broad swipes at an uptight blues "cognoscenti" and cites more dully familiar anecdotes such as the time the Rolling Stones sat at the feet of Howlin' Wolf. A professional musician himself, Wald can regale a listener with pinpoint comparisons of Johnson and Kokomo Arnold recordings that were each waxed more than 60 years ago. Such record-geek soliloquies can clear out a cocktail party, but here they serve a reader well. For Wald is rarely less than convincing when he makes his case for what Johnson and the prewar blues audience were actually hearing in their own day.

Often it wasn't the blues. Repeatedly Wald drives home the point that neither the musicians nor the audience frequenting a Clarksdale, Miss., juke joint in 1937 likely limited their taste to visceral fare like Johnson's "Cross Road Blues." They'd probably never heard it. In Wald's estimation, black listeners tended to prefer the smooth, urbane vocals of the far better-selling (in Johnson's day) blues pianist Leroy Carr, and if the jukebox selections noted by a 1944 field recording team are any indication, some may have liked the "sweet band" leader Sammy Kaye better than either.

In this fashion Wald does not seek to temper admiration for Johnson and his brilliant Delta generation. Rather he wants to rescue them from a historical narrative he sees as having been edited by record producers (the blues were good business), folklorists (the blues were authentic) and Rolling Stones fans (the blues were outlaw), each of which had a separate agenda for the music.

But Wald's focus on folkies and Stones freaks is problematic. For all his interest in the complexity of black-white, blues-pop musical exchanges in the pre-World War II South, he largely ignores that dynamic as carried through to the volatile postwar context. The South is full of tales of white kids who during the segregation era snuck away to off-limits black nightclubs, and of black kids who grew up with their ears tuned to the Grand Ole Opry. Wald is rightly sympathetic to the frustrations of the latter (quoting Bobby "Blue" Bland, "it was the wrong time and the wrong place for a black singer to make it singing white country blues") but oddly uninterested in the experiences of the former. He mentions Elvis Presley mostly in passing and scarcely touches on the impact of postwar black radio. Yet that generation's story had every bit as much to do with evolving perceptions (and misperceptions) of the blues as did any folk revivalism or Stones evangelism.

Nevertheless, the best studies inspire further study, and the best music books inspire further listening. Escaping the Delta could well do both. Blank spots aside, one comes away respecting Wald's view that far too much time has been spent wondering if Robert Johnson really sold his soul to the devil, and far too little time listening at the musical crossroads where he actually lived.

Blues Books @SqueezeMyLemon

Blues Music Books @Amazon.com

No comments:

Post a Comment